## Warning: package 'sf' was built under R version 4.3.3

Shocks, Scandals, and Storms – How Unpredictable Events Influence Presidential Elections

This blog is part of an ongoing assignment for Gov 1347: Election Analytics, a course at Harvard College taught by Professor Ryan Enos. Throughout the semester, we will explore historical election data and use it to forecast the outcome of the 2024 election.

Introduction:

In the high-stakes world of U.S. presidential elections, every detail can seem monumental. Shocks, scandals, and unexpected events can emerge, capturing the public’s attention and potentially altering the trajectory of the election. From personal controversies of candidates to natural disasters, these events test the resilience and adaptability of both the candidates and voters. Some say these surprises don’t make a significant impact, while others argue that they’re often the tipping point that swings votes. This post dives into these moments and examines how shocks, particularly in the form of natural disasters like hurricanes, have affected voting patterns in critical swing states like North Carolina.

The Impact of Scandals on Candidate Perception:

Scandals have always been a wildcard in U.S. elections. While some controversies, like those involving a candidate’s personal or financial life, may make headlines, their effect on voting behavior varies. For instance, some voters may feel disillusioned and withdraw support, while others might dismiss the controversy, rallying around their candidate with renewed loyalty. Research shows that the impact of a scandal often depends on the existing polarization of voters; supporters might stay firm, while undecided voters could be swayed or deterred. However, it’s not just about the scandal itself. How a candidate handles and addresses the issue can often play a bigger role in shaping public perception. This is particularly true for swing states like North Carolina, where voters may not have as strong of a party allegiance and could be more susceptible to a candidate’s behavior under pressure.

Natural Disasters and Election Shifts in North Carolina:

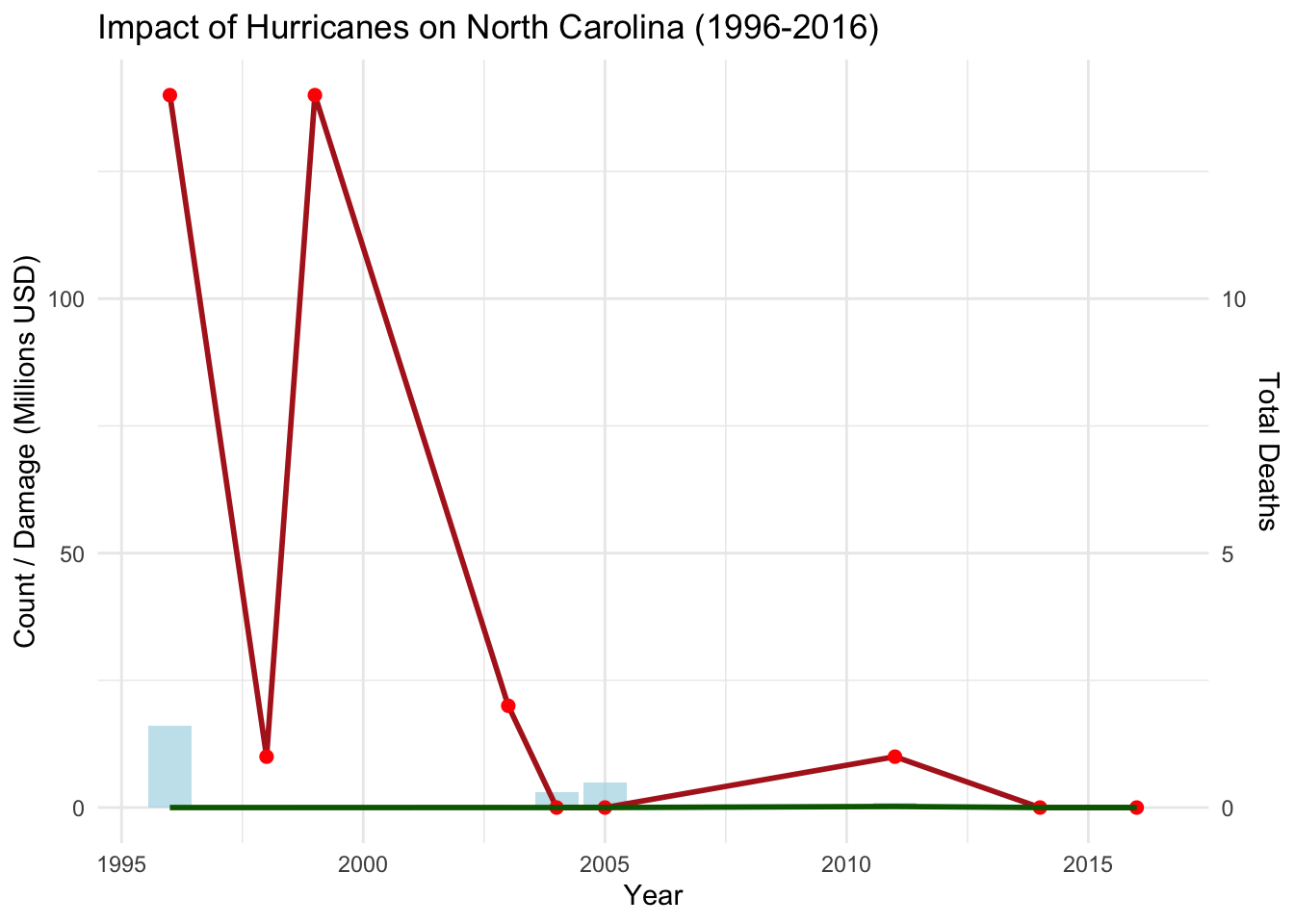

North Carolina is no stranger to hurricanes, with its geographic position making it vulnerable to significant storms that can disrupt lives and economies. When natural disasters hit, they often become political issues, as candidates are expected to address the crisis promptly and propose effective solutions. Public perception of a candidate’s response can be influenced by how quickly relief comes and how well-prepared the state appears. The graph below illustrates the impact of hurricanes on North Carolina from 1996 to 2016. The red line represents the financial damage in millions of USD, while the bars reflect the total deaths attributed to these events over the years.

## Warning: Using `size` aesthetic for lines was deprecated in ggplot2 3.4.0.

## ℹ Please use `linewidth` instead.

## This warning is displayed once every 8 hours.

## Call `lifecycle::last_lifecycle_warnings()` to see where this warning was

## generated.

As we can see, significant hurricane impacts are concentrated in a few specific years. The high spikes in financial damage around 1996 and 2003 indicate substantial hurricane events. However, after 2005, both damage and death tolls appear to drop sharply, suggesting either a reduction in hurricane severity or improved disaster response and infrastructure. This data can imply that voters might have developed different expectations over time, valuing candidates who prioritize disaster preparedness and climate resilience.

How Hurricanes Influence Voting Behavior:

Natural disasters like hurricanes can have a profound effect on voter priorities. For example, after a significant hurricane, voters may lean towards candidates who propose strong disaster response measures or who emphasize climate action, especially if the response to the previous hurricane was viewed as inadequate. In North Carolina, hurricane seasons that brought considerable devastation have, at times, sparked discussions on climate policy and disaster management, potentially swaying voters toward candidates who offer more robust plans. In the context of recent elections, candidates focusing on disaster relief efforts, infrastructure resilience, and community support tend to resonate more with the electorate in regions frequently impacted by hurricanes. North Carolina, being a pivotal swing state, could see shifts in voter behavior based on how well candidates address these pressing issues. In this way, the impact of hurricanes does not just stay in the realm of environmental or economic damage; it spills over into the political landscape, shaping voter opinions and influencing the broader discourse in an election year.

Shocks and scandals may capture headlines, but their effect on elections depends on the context, the timing, and the state of the electorate. In North Carolina, where hurricanes and natural disasters are a recurring concern, these shocks may even play a bigger role than a candidate’s personal scandal. The demands on political leaders to manage crises, deliver swift relief, and build resilience against future disasters can be decisive in how voters choose to cast their ballots. Ultimately, both scandals and disasters underscore the unpredictability of presidential elections and the importance of adaptability in campaign strategies. Whether it’s addressing a scandal or preparing for a hurricane, how a candidate handles these shocks can be the difference between winning and losing key swing states like North Carolina.

Overview on Prediction Model:

In the past few weeks, I’ve been focused on building an ARIMA(3) model to predict national and state poll trends. The ARIMA model, with its ability to capture the autoregressive and moving average components of time series data, provides a dynamic approach to forecasting poll support based on past values and patterns over time. This approach is particularly valuable because polls tend to exhibit seasonal trends and lags that can be captured by the ARIMA model’s lag structure, especially for short-term predictions. By analyzing how previous poll results predict future outcomes, the ARIMA model offers insights into the likely direction of support for the Democratic and Republican parties at both national and state levels.

However, I also wanted to explore a linear regression model as a complementary approach to assess different factors that may drive poll support, beyond just time-series patterns. The linear regression model incorporates variables like past popular vote data, national poll differences, and economic indicators (e.g., GDP growth), allowing me to analyze the influence of these external factors on state-level support for the Democratic party. By comparing the accuracy of both models, I can determine whether a data-driven, time-based prediction (ARIMA) outperforms a model that leverages broader contextual factors (linear regression), or vice versa. This comparison not only provides insights into which approach is more effective for predicting poll support but also sheds light on the importance of temporal versus contextual factors in political forecasting.

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = poll_support ~ D_pv_2016 + D_pv_2020 + poll_support_diff +

## GDP_growth_quarterly, data = dem_polls_combined)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -6.7183 -1.4015 -0.0772 1.2409 9.1749

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 2.6196293 0.1258435 20.82 <2e-16 ***

## D_pv_2016 0.1160315 0.0111364 10.42 <2e-16 ***

## D_pv_2020 0.6762281 0.0110067 61.44 <2e-16 ***

## poll_support_diff 0.9475356 0.0071774 132.02 <2e-16 ***

## GDP_growth_quarterly -0.0164360 0.0008556 -19.21 <2e-16 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 2.2 on 11176 degrees of freedom

## (12434 observations deleted due to missingness)

## Multiple R-squared: 0.9203, Adjusted R-squared: 0.9202

## F-statistic: 3.225e+04 on 4 and 11176 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16

$$\text{Dem_poll}(t,z) = \text{Dem_popvote}(2016,z) + \text{Dem_popvote}(2020,z) + \text{National_poll}(t) + \text{GDP_Growth}(t-Q)$$

This linear regression model predicts Democratic state-level poll support based on past election results, national polling trends, and economic conditions. Specifically, it incorporates the Democratic popular vote in each state from the 2016 and 2020 elections, the daily difference in national poll support between the Democratic and Republican parties, and the previous quarter’s GDP growth. The model shows that recent electoral support in 2020 has a larger influence on current state-level Democratic support than the 2016 results, suggesting that more recent voting patterns are more predictive. Additionally, the national polling difference has the strongest positive effect, meaning that if Democrats lead Republicans in national polls, it tends to increase Democratic support at the state level. Meanwhile, GDP growth has a slight negative impact, which could imply that economic growth might lower Democratic support, possibly due to the perception that a strong economy favors the incumbent party.

Overall, the model performs well, explaining about 92% of the variance in state-level Democratic support. This high R-squared value reflects the importance of these factors in predicting support patterns across states. Each predictor is highly statistically significant, reinforcing their roles in the model. This analysis highlights how past voting behavior, current national trends, and economic indicators interact to influence political support, offering valuable insights for strategic planning and resource allocation in election campaigns.