The Air War in Political Campaigns

This blog is part of an ongoing assignment for Gov 1347: Election Analytics, a course at Harvard College taught by Professor Ryan Enos. Throughout the semester, we will explore historical election data and use it to forecast the outcome of the 2024 election.

Introduction:

In modern political campaigns, the “air war” refers to the strategic deployment of advertisements across television, radio, and digital platforms. These ads are critical in shaping public perception, mobilizing support, and swaying undecided voters. Advertisements allow candidates to communicate their stances on key issues, respond to attacks, and build an appealing image. But the key question remains: does increased advertising truly influence electoral success?

In this post, we’ll explore advertising trends across recent U.S. elections, focusing on party differences in ad tone and volume. Using data from election cycles between 2000-2012 and a closer look at the 2020 election, we’ll analyze whether a larger advertising footprint can be linked to better electoral outcomes. Lastly, we’ll take a look at my updated prediction model to see any correlation between how parties utilized advertisements in the past and if we find a similar pattern in the 2024 election.

Tone of Political Ads Over Time:

Political advertisements are often crafted with a specific tone, ranging from positive promotions to negative attacks. The tone chosen can reveal how a party perceives its strengths and weaknesses relative to the opposition. The chart below illustrates the distribution of ad tones by party over several election cycles.

In the 2000-2012 elections, Democrats and Republicans displayed different strategies in their advertising tones. Notably, Republicans favored attack ads more consistently, while Democrats had a higher proportion of promotional content. This choice of tone might reflect the parties’ perceived need to go on the offensive versus reinforcing their candidate’s positive qualities.

Advertisement Volume and Party Focus in 2020:

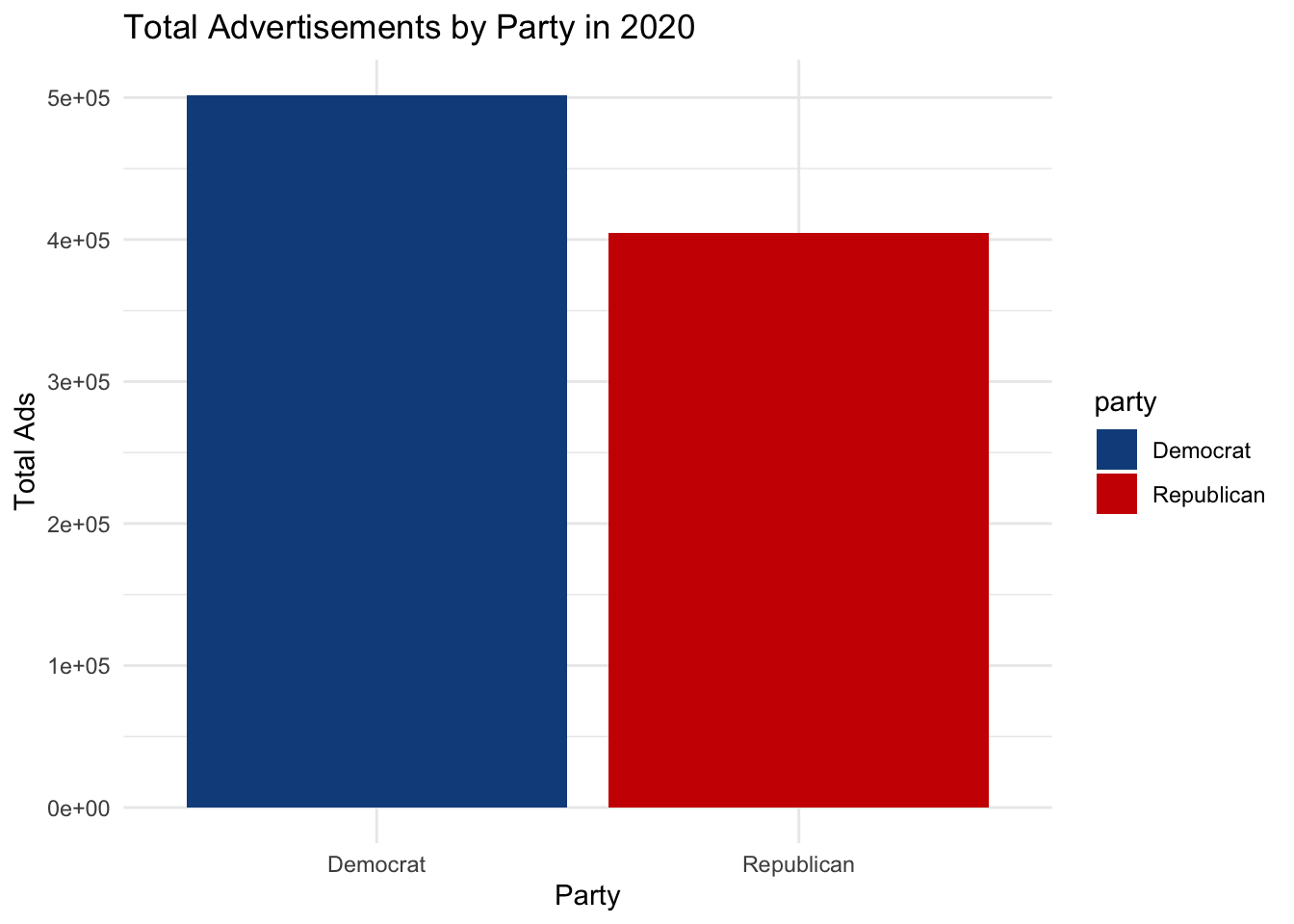

The 2020 election saw both parties ramp up their advertising efforts across various media platforms. As shown below, Democrats aired a higher total number of ads compared to Republicans.

With more than 500,000 ads aired by Democrats compared to Republicans, it’s clear that the Democratic Party invested heavily in the air war for this election cycle. However, the number of ads is just one part of the equation; it’s also essential to consider where and when these ads are placed to maximize their effectiveness. While the Democrats’ strategy of higher ad volume suggests a focus on media presence, the impact of this approach on voting turnout is less straightforward. Research has shown that increased ad spending doesn’t necessarily translate to higher voter turnout.

Despite a larger volume of ads, there isn’t a direct correlation between ad saturation and an increase in people heading to the polls. Voters’ motivations are influenced by various factors, and simply boosting ad numbers doesn’t guarantee a proportional rise in turnout. However, the tone of the adds does effect how voters behave; we see that when adds attack more promote that people tend not vote in general.

The data from 2020 shows Democrats had a significant advertising lead, but this doesn’t necessarily imply a linear relationship with electoral victory. Many other variables, such as grassroots support, campaign funding, and media coverage, contribute to the final results. For instance, despite heavy advertising, candidates who do not resonate with the electorate’s core concerns might still fail to secure a win.

Exploring Political Trends with ARIMA Forecasting:

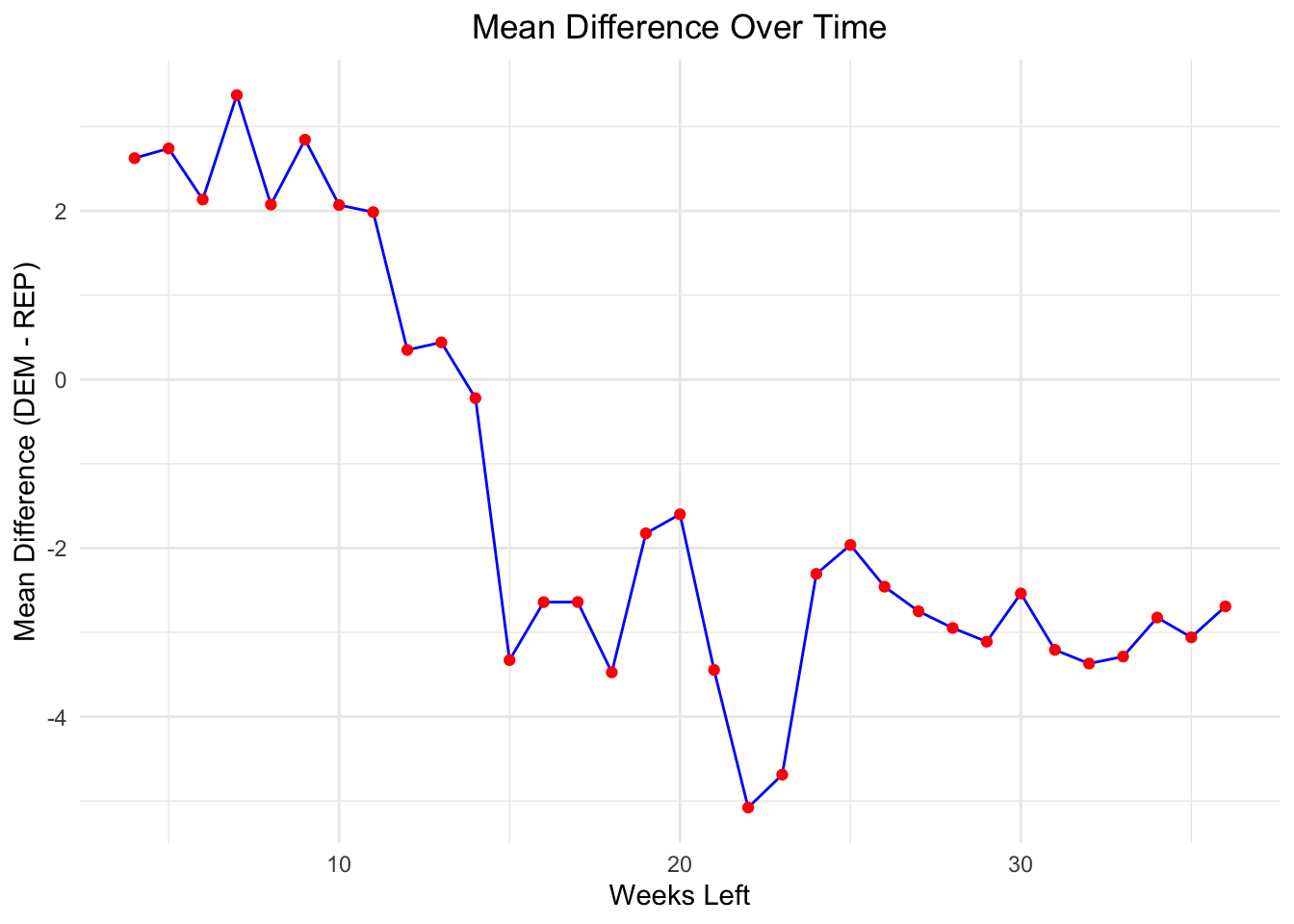

The primary data sources for this model are state-level polls from 1968 to 2024 and the electoral college results for the same period. For this analysis, I filtered the data specifically for 2024 to focus on current trends. This involved merging poll results and electoral college data, calculating the difference in support between Democrats and Republicans, and then aggregating the data by state and weeks leading up to the election.

The variable diff_support measures the difference in mean poll support between Democratic and Republican candidates over time. By tracking this variable on a weekly basis, I can capture how voter preferences change as the election date approaches, giving insights into which party has the upper hand in each state.

Modeling Approach:

I employed an ARIMA(3) model, a type of auto-regressive model that considers three previous time points to predict the next one. Initially, I modeled diff_support at a national level, but then enhanced the model to look at the past 3 week polls, as electoral outcomes can vary significantly from multiple weeks.

For each state, the ARIMA model calculates the expected diff_support value, which indicates whether the Democrats or Republicans are forecasted to lead. This enhanced approach allows for a more granular analysis, which is especially useful in the U.S.

## Series: national_data$mean_diff

## ARIMA(3,0,0) with non-zero mean

##

## Coefficients:

## ar1 ar2 ar3 mean

## 0.9104 -0.0989 0.1174 -0.7453

## s.e. 0.1701 0.2334 0.1722 1.8359

##

## sigma^2 = 1.182: log likelihood = -48.4

## AIC=106.8 AICc=109.02 BIC=114.28

##

## Training set error measures:

## ME RMSE MAE MPE MAPE MASE ACF1

## Training set -0.181042 1.0191 0.762129 2.799254 49.24876 1.013269 -0.05281228

## Point Forecast Lo 80 Hi 80 Lo 95 Hi 95

## 35 -2.451132 -4.335164 -0.5671007 -5.33251 0.4302454

## Time Series:

## Start = 35

## End = 35

## Frequency = 1

## [1] Republicans

As the map indicates, we see variances across states, with certain regions leaning heavily towards one party. However, battleground states show narrower margins, reflecting their historical significance in determining election outcomes. The model’s results suggest that, while some states are predictably aligned, others could swing with last-minute changes in public opinion. We can observe that weeks further away from the election Harris had a strong hold on the polls, but looking at the past three weeks in polls the results show that the closer we get to election day it’s more likely for Trump to win.

Conclusion:

The influence of advertising on election outcomes is complex and multifaceted. While advertisements are essential for visibility and shaping public perception, their direct impact on voting behavior varies. In highly competitive states, where undecided voters may be more susceptible to influence, targeted advertising can play a pivotal role. However, in states with a strong partisan leaning, advertising often reinforces existing opinions rather than changing minds.

The patterns observed in the historical advertising data reflect strategic choices made by each party, often tailored to their perceived strengths and weaknesses. For example, Democrats’ preference for positive promotional ads versus Republicans’ tendency for more attack-oriented messages could be a reflection of how each party attempts to sway different voter bases. The 2020 data, where Democrats aired significantly more ads, underscores a heavy reliance on the “air war” to engage voters, though the ultimate impact on votes depends on factors beyond mere volume.

When correlating these advertising patterns with my ARIMA-based prediction model, an interesting alignment emerges. States with a narrow margin in predicted support between Democrats and Republicans often align with those targeted most heavily by advertisements. This suggests that while advertising may not single-handedly determine outcomes, it likely complements existing trends captured by the model, potentially tipping the balance in closely contested states.

Ultimately, while advertising is a powerful tool, its effectiveness is amplified when used in conjunction with data-driven insights. The ARIMA model highlights which states are more competitive, guiding strategic ad placements that could influence key swing states. Therefore, while advertising alone may not be the definitive factor in winning elections, when combined with predictive analytics, it enhances a campaign’s ability to make informed, impactful decisions.